Did Our Declaration Succeed? (a History At Play newsletter)

What Makes it Successful?

The competencies of a declaration.

Dear History Lover,

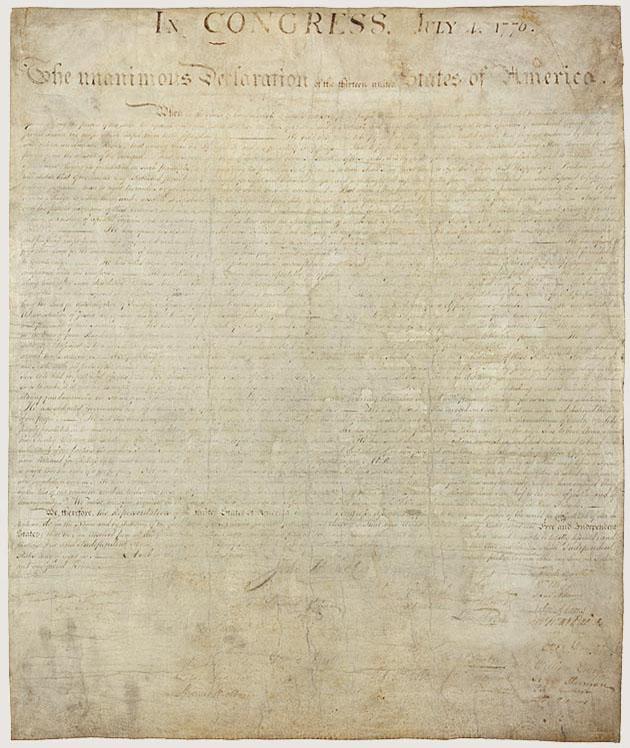

With the celebration of the Declaration of American Independence behind us, we pose the question, “What makes a document successful?” Does the Declaration of Independence actually constitute a success? In fact, the document went public seven years prior to United States’ sovereignty. A revolution still had to be fought and thousands of lives were still taken or in turmoil due to the war. Is that success?

Documents are created in a moment of time to guide governance for the present, as well as the future. What is most challenging is that a document remains stagnant, while the world is in constant flux. People change and, along with them, change the needs of society.

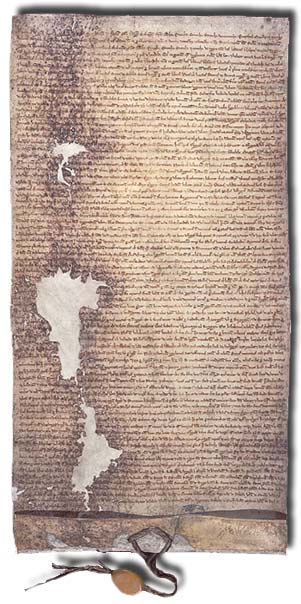

Take, for example, the Magna Carta Libertatum. Its success was in its proclamation to establish that both barons, as well as the monarch King John, were subject to law. Its initial demise, however, came to rise when King Henry III (son of King John) repudiated the rules of the Great Charter, leading to instability and war throughout the region. It is of interest to note that King Henry III was only nine years old upon taking the throne and that his father was said to have signed the Great Charter under duress. The First Barons’ War ultimately led to the exclusion of Clause LXI (61), which allowed barons to rebel against the king if he defied the charter. The charter was later modified by subsequent monarchs based on their needs and desires. While there were several iterations, only three of the original 63 clauses remain intact in English law today. Clause I defends the rights and liberties of the English Church, Clause XIII defends the nation’s customs, and Clause XXXIX (39) provides all free men the right to justice and a fair trial. Although the document, in its original form, may not have stood the test of time, the Magna Carta berthed the idea of individual rights and its influences would be noted in future documents, such as: England’s Petition of Right that combated unlawful taxation; Habeas Corpus, which ensures no person may be imprisoned without reason; as well as the Declaration of Independence. Each document aimed to set precedent and bestow rights to people who had been denied privileges afforded to others. What could not be addressed was how society might change; how people might interpret these laws; or, if the populace would willingly accept their parameters.

Magna Carta, 1225 iteration, issued by Henry III. Wikipedia

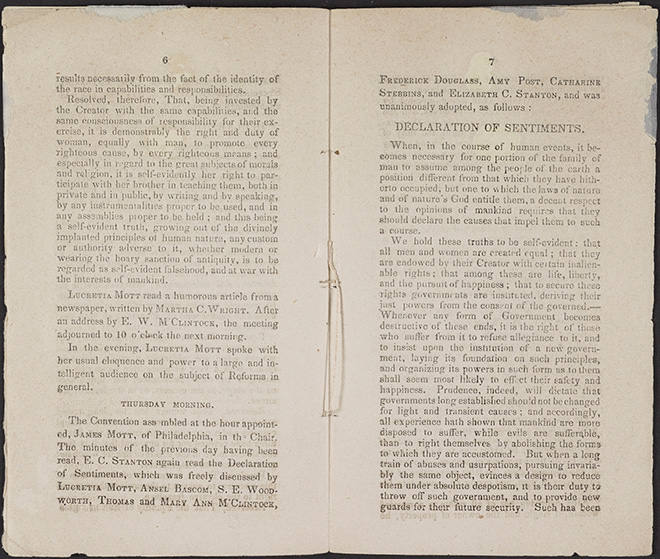

Speaking of accepting parameters, most people interpret the famous words, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” to be an indication of individual rights. At the time of its creation, however, the intent of the Declaration of Independence was to assure that American colonists, as a whole, had the ability to self-govern (a privilege that was extended to the original Puritan settlers when King Charles I signed off on the Massachusetts Bay Colony Charter of 1629). It wasn’t until after the American War for Independence that people regarded the words of the declaration to signify individual equality. Generations later, women would fight for their right to be recognized under the law using many of the same arguments that had been uttered by their fathers of the Revolution. The Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, penned in 1848 by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, insisted that her “right to suffrage is as inalienable as her right to life and liberty.” Stanton’s interpretation and refusal to accept the parameters of the 1776 Declaration brought about a momentous convention at Seneca Falls, where over 300 attendees addressed woman’s issues and led to the first national Women’s Rights Convention two years later at Worcester, Massachusett’s Brindley Hall. Though Stanton’s Rights and Sentiments ignited the Women’s Movement, it would take an unjustifiable 72 years before the passage of the 19th Amendment prohibited voting discrimination on account of sex. Should we interpret nearly three quarters of a century of waiting to indicate success?

As society continues to shift at a break-neck pace, might there ever be a document that satisfies societal justice and successfully engenders immediate change, simply with the stroke of a pen or a keystroke? Perhaps the measure of success is not how quickly society adheres to a declaration, nor may it be its tenure, but rather, its ability to inspire a collective intellectual shift which shall evoke real change.

Historically yours,

Judith “Jude” Kalaora Judith@historyatplay.com

Founder | Artistic Director History At Play, LLC

Research and Collaboration by HAP Intern Ani Valentino.