Peering into History with Public Art

For the month of October we explored Public Art’s Role in Shaping Historical Memory for our History At Play newsletter. Below is my original research and writing for HAP.

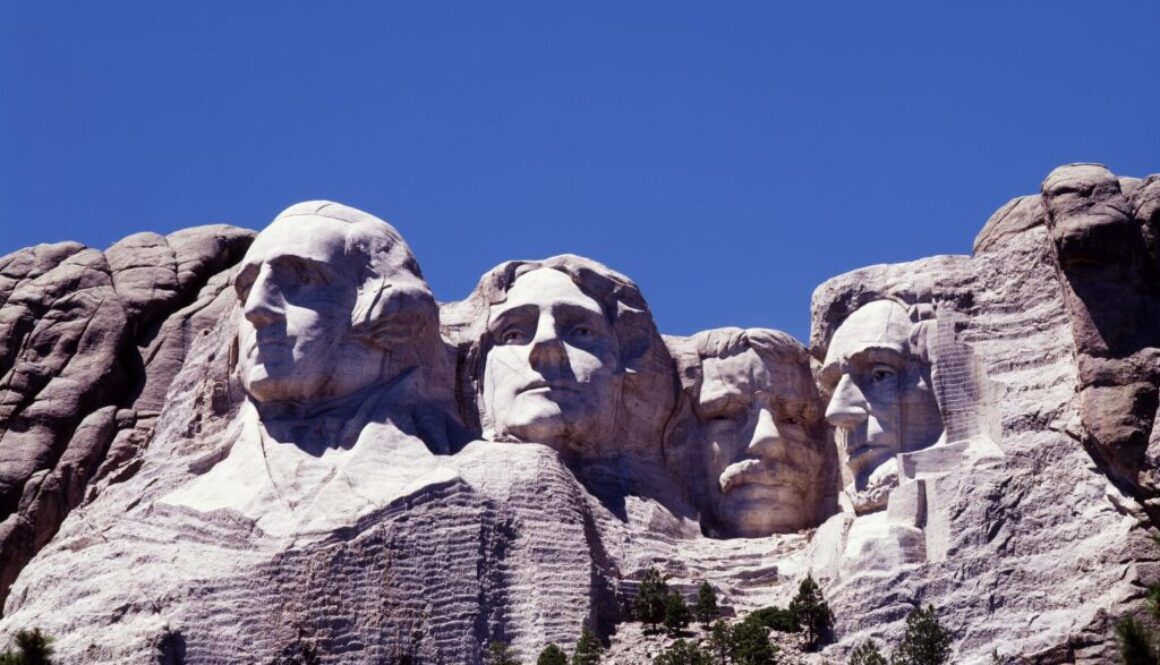

With Indigenous Peoples Day behind us, formerly celebrated as Columbus Day, we explore the role of public art in shaping historical memory and minority representation. Throughout history, we have often honored historical figures and significant historical events through art and memorials. Yet, these monuments were funded by those in power reflecting a singular point of view. In Ancient Greece and Rome, statues were used as propaganda to promote the leaders and their agendas of the time. The Renaissance witnessed a flourishing of artistic expression, driven by the wealthy. These people, often political or religious leaders, maintained immense influence over the content and themes depicted in public art. As a result, public art became a reflection not only of artistic skill, but also of the agendas and aspirations of the privileged elite. In the 20th century, public art was a critical tool for propaganda. During Hitler’s regime, the Nazis manipulated art to glorify Arayan supremacy and demonize those who did not fit the standard. Similarly, the Soviet Union utilized monumental sculptures and murals to project an image of strength and unity, suppressing dissenting voices. In our nation’s history, from Civil War statues to Mount Rushmore, art has been used to portray a singular version of the truth. It has been used to elevate chosen voices and silence others. It is essential to consider the perspectives of all communities and ensure that art reflects the culture and history of the people, location, or event in a meaningful way.

Many argue that art is subjective, while others stake ownership in the history that art represents. In New York City, the statue of Christopher Columbus is controversial to many. Some in the Italian American community believe that he was an essential figure in the founding of America, omitting the horrendous acts he committed against indigenous people, and the fact that he never set foot in North America. To indigenous people, he was a tyrant who brought disease and violence. Debates have come up on whether to rename the famed Columbus Circle and take down his statue. From the same lens, we examine Mount Rushmore. It is crucial to address the fact that Grandfather Mountain, the very site on which it was erected, was unlawfully taken away from the Dakota and Oceti Sakowin people during the 1800s. Harriet Senie, a renowned art historian, said, “It’s important to invent alternative pasts for a culture that finds it hard to accept the real one. It’s paradoxical that a Shrine of Democracy is placed in the center of land acquired through a well documented blatant example of 500 years of genocide and hemispheric conquest. Mount Rushmore implies that the Europeans have always been here.” Mount Rushmore has further erased the culture and traditions of the Dakota and replaced it with a whitewashed narrative.

Public art is powerful. The 1993 monument, “Danzas Indigenas” by Judy Baca, honors the indigenous, Spanish and mestizo people that were in Baldwin Park, CA prior to the arrival of Europeans. The piece was commissioned to reflect the diverse cultures of the City of Baldwin Park past and present. According to Baca, “Its intention was to become a site of public memory for the people of Baldwin Park; to make visible their invisible history.” One way it achieves this goal is through the many quotes included, statements made by local residents. The monument, an archway designed in part to reflect the nearby San Gabriel mission, sparked controversy years after its inception. The anti-illegal immigration organization, Save Our State, protested for the removal of quotes such as “It was better before they came” and “the kind of community that people dream of rich and poor, white, brown, yellow all living together.” They believed these statements to be “anti-American” and “racially-charged.” According to Baca, “This statement “it was better before they came”, was deliberately ambiguous. About which “they” is the anonymous voice speaking? The statement was made by an Anglo local resident who was speaking about Mexicans. The ambiguity of the statement was the point, and is designed to say more about the reader than the speaker – and so it has.”

Public art mirrors society, and reflects the power dynamics and narratives of its time. While celebrated for its capacity to inspire and challenge, it cannot be divorced from its role in shaping historical memory and reinforcing dominant ideologies. Understanding this dynamic prompts a critical engagement with public art, urging us to dismantle exclusions and embrace a more inclusive, representative future. As our society begins to view art with a different lens, one in which historical truths are visible, public art can be used as a tool for social change, raising awareness for historic wrongs, building empathy for marginalized communities, and instilling a greater understanding of humanity.

###

For More Historical Insight subscribe to the History At Play newsletter.