Holidays or Holy Days? The Evolution of the Season of Giving

For the month of December we explored Holiday History, The Evolution of the Season of Giving for our History At Play newsletter. Below is my original research and writing for HAP.

###

As one prepares to bestow gifts this season, we reflect upon the origins of the winter holidays. In contemporary society, the emphasis has shifted from religious roots to consumer-driven frenzy, centered around the exchange of gifts. The spirit of the holidays is intertwined with bustling stores, dizzying credit card bills, and corporate capitalization on material sales.

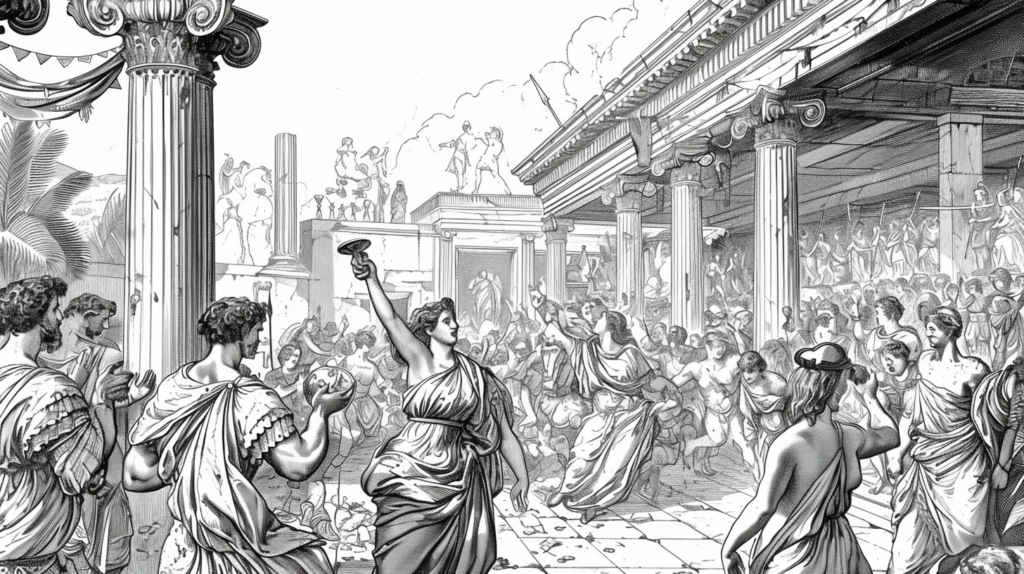

Christmas customs originate from ancient Roman festivals, such as Saturnalia; a two-week celebration for the god Saturn; the birth of Mithra (the Roman sun god); and the pagan custom of lighting bonfires and candles. Ancient Romans celebrated Saturnalia and the birth of Mithra with great joy, creating a festive environment similar to the lively celebrations of Mardi Gras. Simultaneously, it was a logical time to celebrate, as beer and wine were fermented and ready to drink and large quantities of meat had been slaughtered, but not yet salted for preservation. As Christianity spread through Europe, clergy were unable to halt pagan celebrations. As a result, the church incorporated elements of Paganism to merge with their own Christmas rites.

In England, Christmas was celebrated until the mid-1600s, when the holiday was banned. During this time, Protestants were suspicious of Catholicism and believed the festivities to be too closely associated with the Catholic Church. This led to the passing of a Parliamentary ordinance, prohibiting the Christmas celebration. However, the ban was short-lived, as the prohibition came to its end with the restoration of the Stuart Monarchy.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Christmas featured feasting, masking, dancing, carding and dicing (i.e. gambling), and church services. Caroling was also popular, with wassailing being an important part of an English Christmas, though carolers existed even earlier in the form of “Watchmen” or “Waits.” Watchmen were hired by municipalities to patrol neighborhoods and warn the community of danger or emergency. When a municipality experienced fiscal hardship, watchmen were often the first to be cut from the budget; thereby, forcing the watchmen to change their tactics and beg for money by waiting outside a home and singing until the inhabitants would donate to their cause. As economic conditions improved, the ritual morphed and wassailing involved people strolling from house to house to offer a bowl of hot cider or ale to their neighbors, whilst singing carols to wish them good health. In America, 17th Century settlers brought many English traditions related to feasting, caroling, and holiday decor. When Dutch immigrants settled in New Amsterdam (i.e. New York) in the 1600s, they brought the tradition of Sinterklaas, a saint who distributed gifts to children.

Within the Northeast region of America, the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted a law, in 1659, called the Penalty for Keeping Christmas. It stated “festivals as were superstitiously kept in other countries were a great dishonor of God and offense of others.” Puritans believed every day was Christ’s day and it was sacrilegious to celebrate his birth by engaging in licentious activity and forbearing labor. The ban impacted celebrations in Massachusetts for years to come. In the 19th Century, German immigrants imported the custom of decorating trees and the Christmas holiday regained popularity in the United States once Civil War propaganda illustrated Santa Claus visiting the Union Army. In 1862, cartoonist Thomas Nast drew a picture of jolly old Saint Nicholas giving gifts to children for the cover of Harper’s Weekly, and in 1870 Christmas became a federally recognized holiday.

In the 20th Century, the rise of department store marketing campaigns saw Macy’s and Coca-Cola in a mutual marketing ploy to popularize Santa. Macy’s invited “Santa” to visit their stores, while Coca-Cola selected him as their holiday representative. Soon, ornaments, stockings, and other decorations depicting his image were monetized. During this period, Eastern Europeans immigrated to the USA following World War II. By the 1950s, Jewish families even had Christmas trees in their homes and young Jewish children sang carols with their schoolmates in order to assimilate. The celebration of the rededication of the ancient Temple Mount in Jerusalem was replaced with Christmas traditions. As the subsequent generation of American Jews resisted these practices, religious leaders sought to reestablish Chanukah and its religious roots, but the excitement of gift-giving had already taken hold. Rather than removing the new tradition, Chanukah incorporated gift-giving into its “Festival of Lights.” In addition to lighting a new candle for each of the eight nights that one night’s worth of oil burned, parents offered their children an accompanying gift. Chanukah commemorates the Jewish Maccabean Revolt against the religious repression of the Seleucid Empire (the Seleucid Empire encompassing modern-day Greece and surrounding territories). Specifically, the celebration honors the rededication of the Second Holy Temple of Jerusalem, which was under the dominion of the Jews dating back to Maccabean Revolt of 167 to 160 B.C.E and beforehand, located in modern-day Israel. Soon, big department stores were advertising Chanukah menorahs, candy gelt, and dreidels alongside Christmas stockings, candy canes, and wreaths.

While businesses continue to market the magic of the December holidays, they have permuted and diluted that original magic – that of spirituality, HISTORY, and community. What remains is a season centered around consumption rather than faith or cultural identity. The evolution of these winter celebrations makes it clear that with commercialization, holy days become holidays in the most materialistic sense.

###

For More Historical Insight subscribe to the History At Play newsletter.