Working Over Time

The Development of Standardized Systems

As we reach the culmination of the first month of 2024, we explore the origins of the modern calendar and its influence . In Ancient Egyptian and Babylonian Society, time was organized by the natural seasonal cycles. In these early societies, tracking time was used to support food productivity. Dials and obelisks monitored the position of the sun, signaling the beginning and end of the workday. The Mayans and Romans developed intricate calendars grounded in natural cycles, reflecting their interconnectedness of time with spiritual beliefs and social structures. The Mayan calendar, composed of the Haab, Tzolk’in, and the Calendar Round, was intricately intertwined with lunar, astrological, planetary, and human cycles. The Julian calendar was a solar calendar proposed by Julius Caesar in 46 BC which laid the foundation for our modern Gregorian calendar. With 365 days in each year, the calendar, marked by 12 months and a leap year every four years, the Julian calendar exemplifies an early attempt at standardization of time.

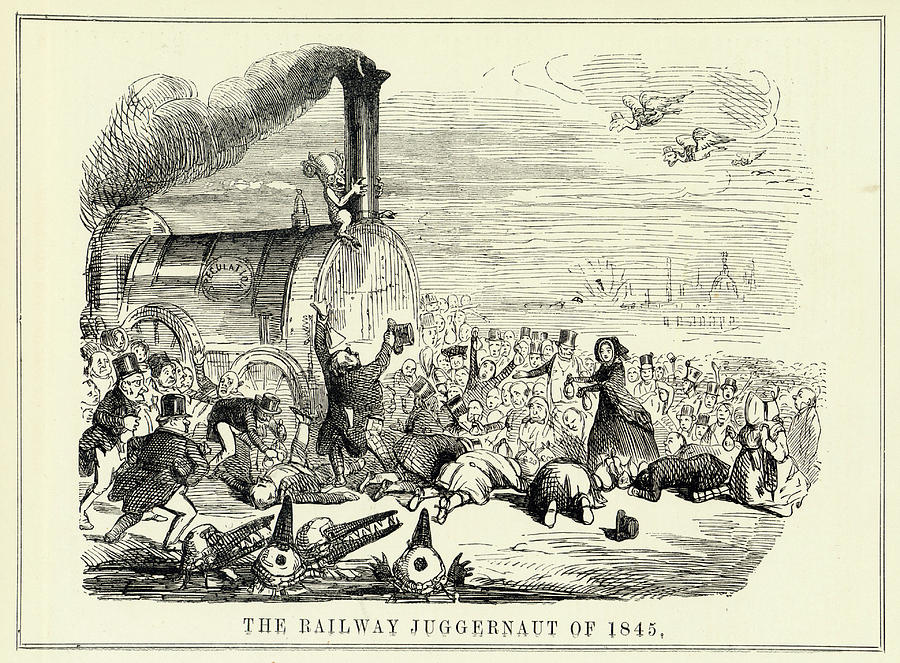

More recent notions of keeping time evolved alongside the rise of capitalism and in support of economic development and wealth generation. Widespread standardization came as a result of industrialization, as factories and railroads demanded efficient logistical coordination. The regimented clock replaced seasonal rhythms with “uniform time.” Punching clocks monitored factory work hours, creating the mentality that “time is money.” The concept that profit can be generated through increased working hours emerged. In 1883, American railroads instituted time zones for safety, which influenced a broader societal adherence. Prior to standardization, cities and towns had the ability to set their own time, which was often displayed for the public to see on government and religious building establishments. This standardization of time was crucial for coordinating complex transit and freight schedules and ensuring safe and efficient travel. Subsequently, it also served to promote forced structure on human activity.

As capitalist values elevated productivity, our relationship with time became profit-driven. Employees trade their “hard earned time” for fiscal compensation, sometimes working “overtime” or “double-time” to increase their earnings and by relegating certain hours of the day to be more valuable than hours by increasing pay rates. The use of time is critical to capitalist societies with economic systems known for habitually pushing efficiency and productivity. The emphasis on efficiency has revolutionized the organization and execution of labor, resulting in an establishment of rigid work schedules and intensification of labor in order to get things done “on time.”

By the 1960s, governments and businesses relied on technology to manage time. Early computer programs relegated two digits to represent the year. In late 1999, as we approached the year 2000 and a new millennium, many feared that computers would misinterpret “00” and cause a major glitch, potentially crashing the stock market, impacting travel, and resulting in huge financial loss and malfunction across the globe. The system which had been recently created to efficiently manage time was about to disrupt it. Software and hardware companies raced against the clock to resolve the feared “Y2K Bug.” Ultimately, their collective solution was to convert the two digit representation of years to four digits.

And speaking of the fixation on time and how it affects the New Year, consider our approach to New Year’s resolutions. The tradition of New Year’s resolutions even plays into capitalist values of self-improvement tied to output and growth. There is societal pressure to: set ambitious goals; obtain memberships to join pricey health and fitness clubs; and invest in new clothing, home improvement, and even fad diets. The tradition of tying resolutions to spending and productivity perpetuates capitalist ideals for constant growth even at the individual level. From ancient civilizations organizing time around agricultural seasons to industrialization giving rise to standardized time, the modern calendar has evolved to prioritize productivity and efficiency. Ultimately, the calendar that once reflected natural cycles and spiritual connection has become a dictator for work and a harness to measure personal growth. While establishing a sense of order and predictability, standardized time has also accelerated society’s focus on profit over purpose. As we prepare to embark on this leap year, it is vital to reflect on how we can recapture a more balanced relationship with time. Though recalibrating ingrained notions of productivity will prove challenging, maintaining awareness of its origins allows us to reshape the role of time in our lives. It is time to prioritize well-being over wealth.

To read the published version visit History At Play, and consider subscribing to the monthly newsletter.