Do You Feel Lucky?

From the Ancient Egyptians carrying scarab beetle amulets to modern-day athletes donning their favorite socks or undergarments, humans have long been captivated by the concept of luck. This enduring fascination, which defies logic and transcends culture, reveals a deep-seeded desire to understand and influence the unpredictable forces that shape our lives. While some dismiss lucky charms as mere superstition, the concept of luck continues to hold weight, offering a sense of control in a world of uncertainty.

Ancient civilizations, including those of Egypt, Greco-Rome, Southeast Asia, and Orient used amulets and talismans made from various metals, such as gold and silver, as well as precious stones. One of the oldest symbols of fortune is the swastika, with its origins spanning back over 5,000 years. Long before its perverse association with the Nazi regime, the swastika represented divinity, spirituality, and well-being across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism religions as well as schools of thought. The word ‘swastika,’ derived from the Sanskrit word ‘svastika,’ means “conducive to well-being.”

The influence of religious weight on symbols of luck is profound, with many cultures incorporating artifacts into their charms for protection and prosperity. Whether a Hindu yantra, a Christian crucifix, an Islamic crescent moon, or a Turkish bonjuk (evil eye), the integration of religious artifacts as symbols of luck is guided by a deep-rooted belief in a higher spiritual power that can be held responsible for our protection and guidance.

Folklore and superstition also play a crucial role in the development of lucky symbols and the rituals that surround them. Take the humble horseshoe, for instance. Although its exact origins are unknown, many believe it emerged as a symbol of luck to honor St. Dunstan, the English saint of blacksmiths. One version of the tale depicts the devil, disguised as a horse, visiting St. Dunstan for new shoes. Recognizing the satanic shapeshifter, St. Dustan hammered a scorching hot horseshoe onto the devil’s hoof. Howling in pain and under duress, the devil relented and promised to never enter over a threshold with a horseshoe nailed above it, fearful of the scorching crescent-shaped talisman. Over the centuries, countless households have nailed horseshoes over their doors, to protect their domiciles from evil, forging this charm into contemporary folklore and popular culture.

Even Judaism, which decrees that one may never worship an idol nor object, sees many followers placing a mezuzah— a small and sometimes ornately decorated container with a prayer scroll inside— on the doorposts of homes. The tradition spans back many thousands of years. Upon exodus from Egypt in 1310 BCE, Jews were commanded to mark their domicile with the blood of a sacrificial lamb, thus signaling that the Angel of Death ‘pass over’ their home, sparing their firstborn from death due to lethal plagues. The practice became the origin story for the etymology of the ‘Passover’’ holiday, which recalls the Jewish peoples’ escape from slavery under Egyptian rule. The mezuzah not only replaced archaic sacrifice, but it also provided a tangible reminder that separates the outside chaos of the world from the peaceful sanctity of the home. Some believers touch the talisman upon crossing the threshold, and in certain places, like Turkey, prayers are recited for health and success as one leaves the home. The mezuzah remains a powerful symbol of faith, protection, and luck for households to this day.

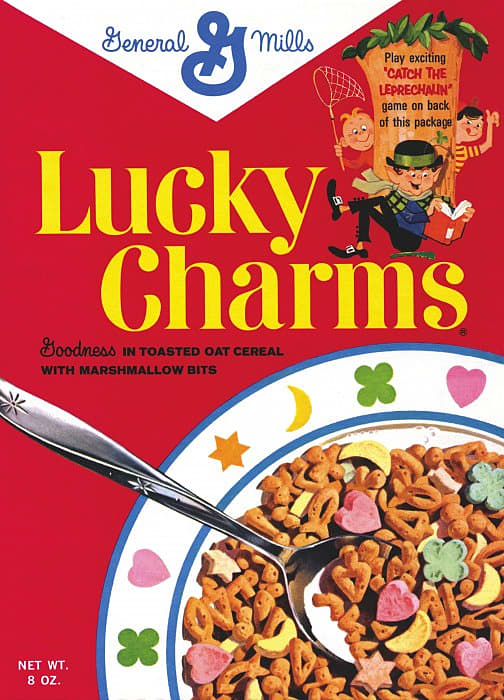

In contemporary commercial culture, lucky symbols have become widely used in advertising, branding, and consumerism. Look no further than General Mills’ iconic “magically delicious” cereal Lucky Charms. In 1964, product developer John Holahan devised a clever way to enhance plain oat cereal by adding a whimsical leprechaun mascot and sprinkling in marshmallow shapes, such as four-leaf clovers, rainbows, and purple horseshoes (added in 1983). Companies use the prospect of luck to increase profit and create a sense of optimism for consumers. This has caused a noticeable shift in how symbols are perceived, with modern interpretations often deviating from more traditional origins. For instance, legend says that St. Patrick used the shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity when he introduced Christianity to Pagan Ireland in 432 AD. Today, the cultural importance of the shamrock is overshadowed by its commercialization leading in to St. Patrick’s Day, attracting patrons to frequent bars serving green beer, with kitschy costumes, and “Kiss me, I’m Irish” shirts adorning its celebrants.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/71/5271b0a1-d4f8-4826-8a75-c195bb16f435/patrick.jpg)

From ancient antiquity to modern commercialization, luck has swayed our beliefs and actions. While some view it as superstition, even the most incredulous may possess objects of sentimentality. Whether seeking comfort in a family heirloom or embracing a new ‘chachky,’ the allure of good luck symbols showcase a blend of history, lore, and ritual. Perhaps the truest luck, however, lies in our unique capacity to manifest our future. If one’s ability to catalyze good fortune is emboldened by tossing a penny into a wishing well, then so be it.

We wish you luck, health, and history this Springtime.

Read the published post at History At Play!