What is the Price of Progress? (a History At Play newsletter)

The Evolution of Education

The Price of Progress

Dear History Lover,

As weather cools in the northern United States, students around the nation, as well as the world, have returned to school. Education has undergone monumental change since the first formal schools were established in 17th Century America. While major strides have been made in accessibility and inclusivity, significant gaps remain in terms of equality and affordability.

When the Puritans settled Boston, Massachusetts in 1630, they formed the first public school five years later. Boston Public Latin School was revolutionary in the sense that it was tax-supported and, thus, offered free admission to male students (female students not being admitted until the institution co-educationalized in 1972). Puritan objectives emphasized the democratization of education, stating:

“… God had carried us safe to New England, and we had builded our houses,… one of the next things we longed for and looked after was to advance Learning…” “… under the spirit of religion…,”

Boston Latin was intended to prepare students for Harvard, which upon its establishment in 1636, was a divinity school. At the time of its inception, many parents chose not to send their children to Boston Latin, believing agricultural work and family business took precedence. As a result, the General Court passed the Massachusetts Bay Educational Law in 1642, stating that children needed to “read and understand the principles of religion and understand the capital laws of the country, and to impose fines on all those who refuse to render such accompt to them when required.”

Boston Latin School flourished thereafter, though the narrow scope of gender inclusivity benefited less than half the population. It did, however, foster the growth of a middle class, which would go on to reevaluate its relationship with the crown over a century later. The boldness of a people to make demands of a monarch could only come from a populace that understood their rights as Englishmen and women, whereas the general population of 17th Century England saw widespread illiteracy, poverty, and peasantry. Without education, enslaved peoples cannot fight for freedoms.

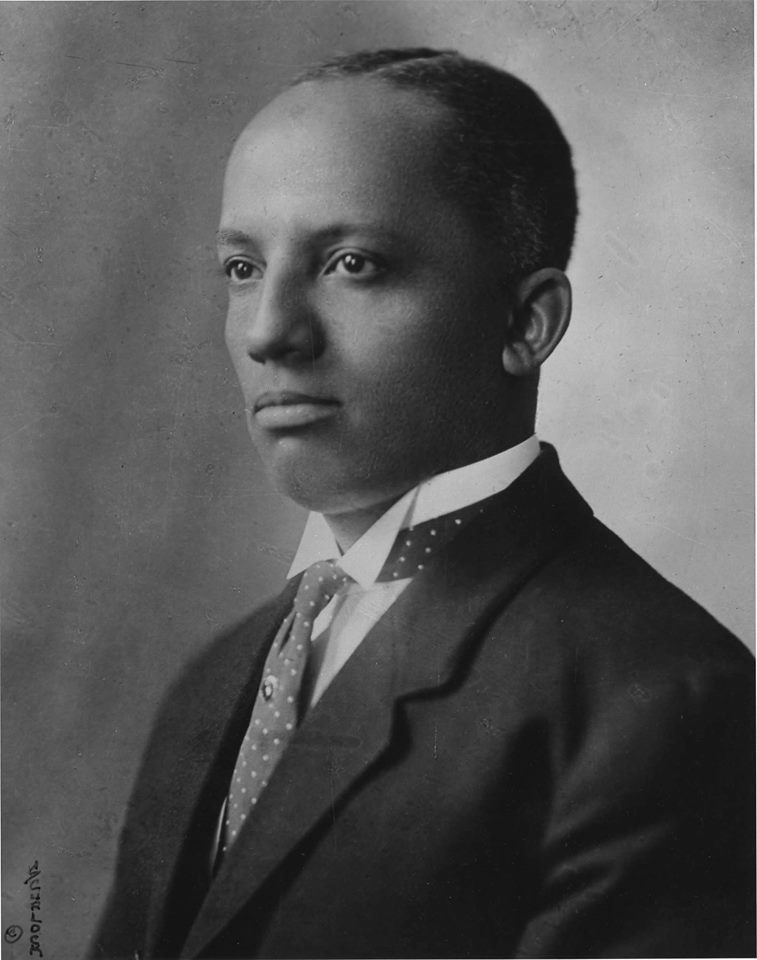

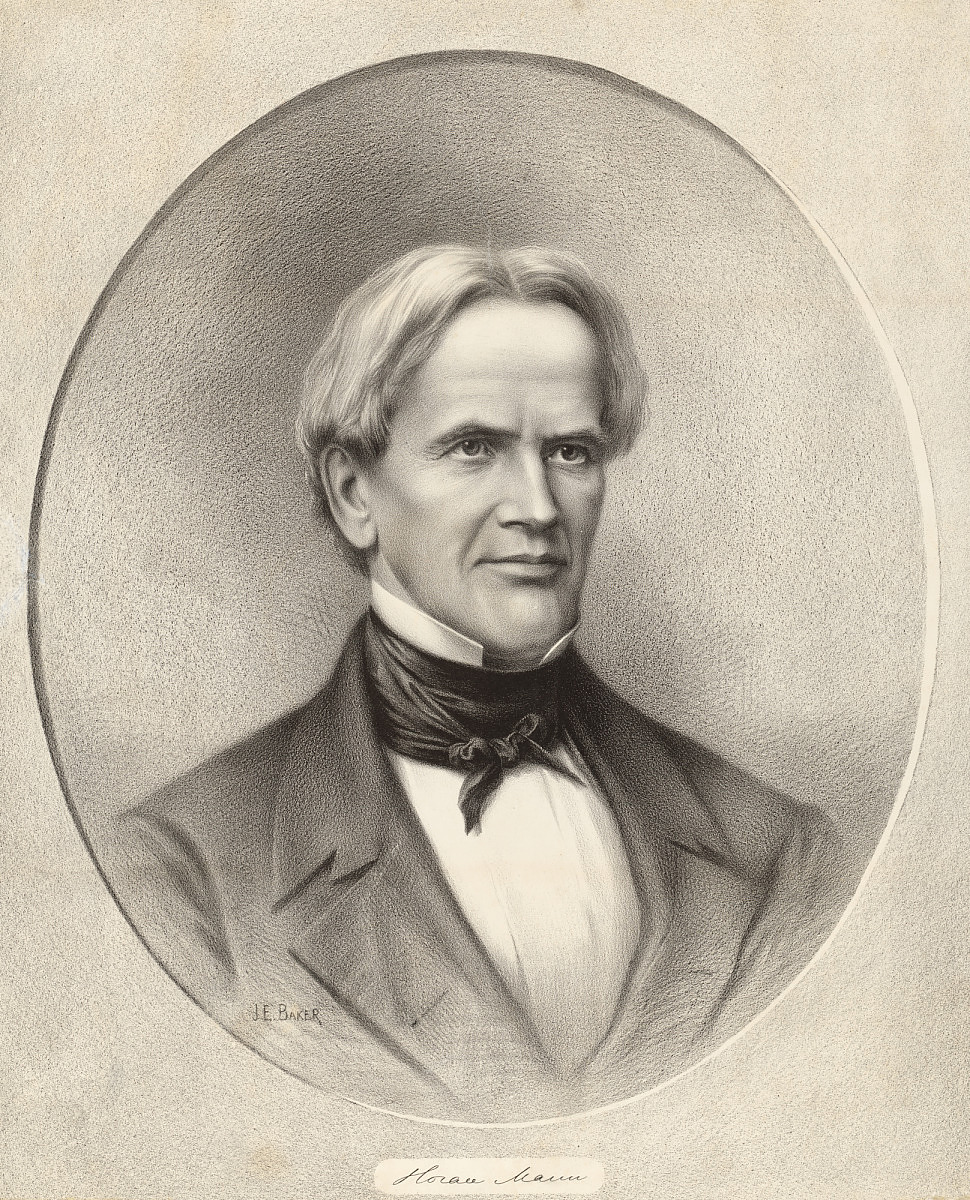

American educational accessibility came slowly. It was not until the 1830’s that Horace Mann, “Father of Public Education,” pioneered the Common School Movement, arguing that every child deserved a publicly-funded basic education. Mann recognized that improvements required formal teacher training and oversight. His vision for broad public education, accessible to all children, regardless of social, racial, and gender backgrounds was profound. Nearly eighty years later, in 1907, Italian physicist and educator Maria Montessori opened the Children’s House, a school with a hands-on learning approach.

Over time, emphasis on students with developmental challenges also evolved. Christa McAuliffe, commonly remembered as the Teacher in Space, chose to pursue a Masters Degree in Policy Supervision and Administration and entitled her thesis The Acceptance of the Handicapped Child in A Regular Classroom by His Normal Peers. Submitted in 1978, the thesis speaks to the fact that McAuliffe witnessed deficits in support for students with mental and physical challenges. Key 1990 legislation, such as the Disabilities Education Act (previously known as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, 1975), cemented equal access into law, fostering education as a fundamental right for all.

Presently, the greatest obstruction to equal-access schooling is the soaring cost of higher education. It is reminiscent of the aforementioned inequities of 17th Century English education reserved for nobility. While colonial-era Harvard relied on private endowments rather than public tuition, private universities in the United States now exceed $70,000 per year per student. Even public four-year colleges average over $10,000 per year in tuition and fees. Students rack up massive debt in a futile effort to fund their futures.

While resources like financial aid, merit & academic scholarships, and vocational programs alleviate some of the burden, sweeping reforms are needed. Rather than determining the morality of forgiving student debt, perhaps one should prioritize the ethics of affordable action in education. The future of the nation relies upon a relinquishing of the capitalistic trajectory of higher ed and a return to the true democratization of education with an emphasis on federal funding for its support.

Historically yours,

History At Play™, LLC

judith@historyatplay.com

Judith “Jude” Kalaora

Founder | Artistic Director

Research, writing, & collaboration by HAP Intern Ani Valentino and formatting by Marketing Coordinator Olivia Winters.